Category Theory for the rest of us coders

- You’ve heard category theory is powerful.

- You’ve seen the diagrams.

- You have no idea what’s going on. Let’s fix that.

Why Category Theory seems hard

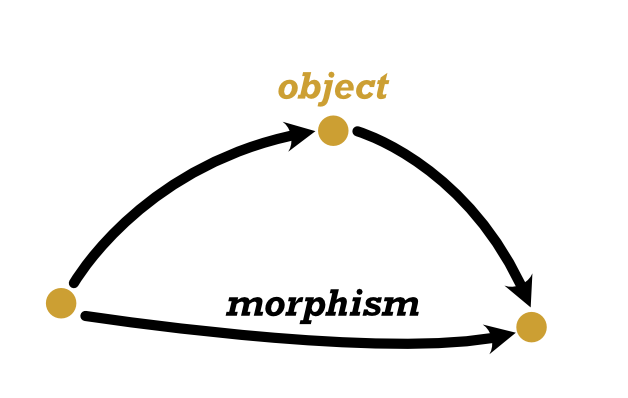

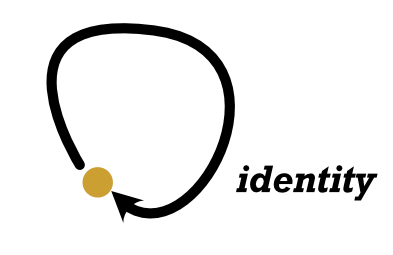

Whenever someone starts describing category theory, it seems to start out pretty slow, basically like 7th grade math. Categories have objects. There are relationships between them called “morphisms”. You can compose a sequence of morphisms to create another morphism. And every object has an “identity morphisms” starting from itself and going to itself such that you can insert any number of identity morphisms in a sequence without changing the overall morphism. That’s kind of it.

The reason it starts getting hard is because the next thing people do is illustrate categories using topics from Abstract Math. They’ll say it’s like an Abelian group or a ring or a monoid. They’ll talk about differentiable manifolds and homologies. But what makes this particularly hard to follow is that each topic has its own notation and in order to understand all the examples, you’ll need to grab a textbook for each one. So now you have a pile of problems: what does the categorical concept mean, what does the abstract math illustration mean, what does the notation mean, and how do you map the categorical concept into the abstract illustration.

Let’s make Category Theory concrete using code as our category

I don’t think we need to do that. The wonderful thing about abstract math is that it must also apply to concrete cases. So let’s skip over the Group Theory and Topology and go right to what we know how to do: code. We can define a “Coding Category” where the objects are whatever you can assign to a variable (records, documents, arrays, numbers, strings, etc.) and morphisms going from $x$ to $y$ mean this: given $x$, I have enough information to write the code to come up with $y$. Note that identity morphisms automatically make sense. Composing a sequence of morphisms also makes sense: if given $x$ I can write code to compute $y$, and given $y$ I can write code to compute $z$, then given $x$, I can write code to compute $z$. Unlike the general case where morphisms express relationships between objects, in the coding category we can view morphisms as transformations from one object into another.

Examples

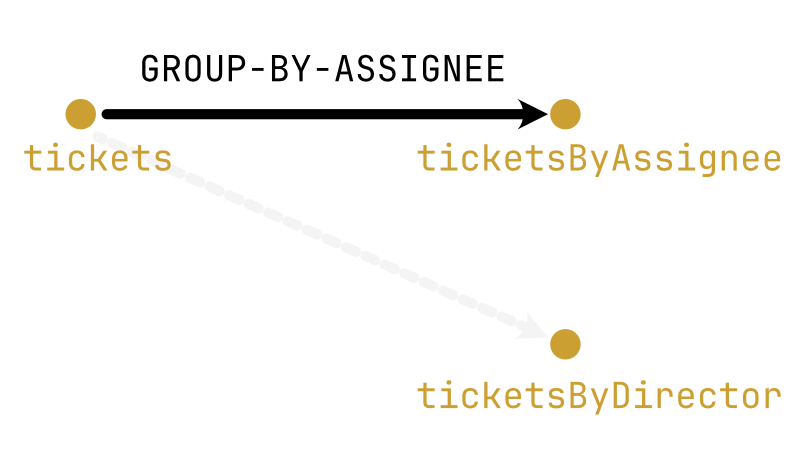

Let’s look at a couple of examples. Suppose tickets is a list of Jira tickets. If we wanted to generate a report that listed tickets summarized by assignee, we’d need something like ticketsByAssignee whose keys are ticket assignees and whose values are a list of tickets assigned to that person. Clearly, it’s possible to write code that takes tickets and returns ticketsByAssignee—we have all the information to do it. And so, there’s a transformation from tickets to ticketsByAssignee. A good name for this transformation is GROUP-BY-ASSIGNEE.

Now suppose we had another section of our report that summarized these tickets by the director of each division. To construct this, we’d need something like ticketsByDirector. Do we have enough information to code this up from tickets alone? No, because tickets doesn’t have any organizational data in it. So there’s no transformation from tickets to ticketsByDirector.

Closing thoughts

Lots of smart people have worked out relationships and structures that apply to a vast array of categories. By defining a bona fide Coding Category, we can apply all of these results to help us design and solve coding problems in a new way. Viewing code categorically is a paradigm shift, but by doing this, we can understand Category Theory from a concrete coding perspective and apply it to solve real problems in a practical way. We’ll take more about this in our next post.