Solving problems is about finding inverses

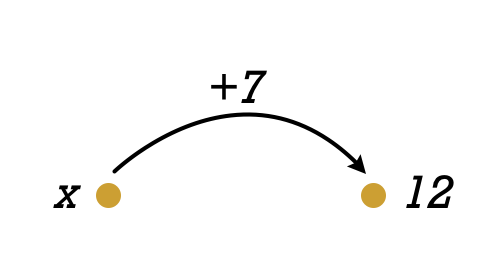

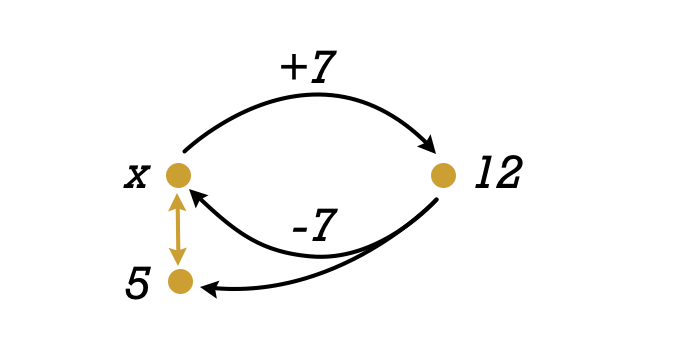

Last time, we touched on solving coding problems and hinted at what it means to solve problems in general. A good place to start is with something simple. Suppose we wanted to solve $x + 7 = 12$. If you think about it slowly and carefully, you’ll realize that the essential operation is finding the inverse of $+7$ and applying it to both sides of the equation.

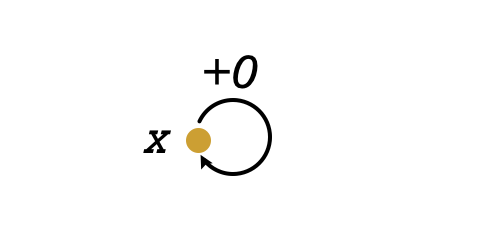

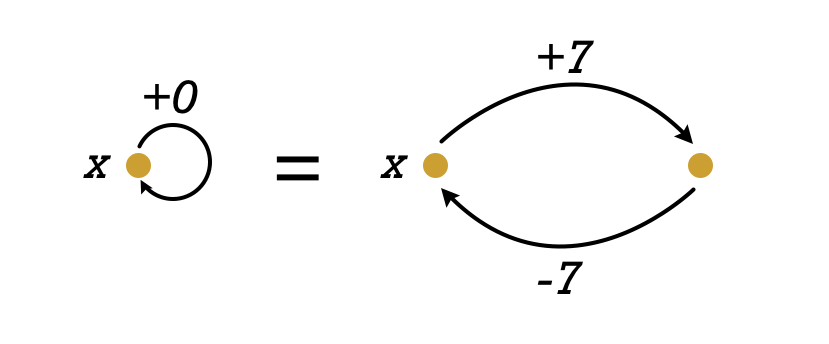

The inverse of a transformation undoes it so that the net result “does nothing.” What “doing nothing” means depends on context. For addition, doing nothing means adding zero—so the identity transformation is $+0$.

To invert $+7$, we apply $-7$, since composing them gives $+7 - 7 = +0$. The identity transformation matters because it lets us isolate what we’re solving for: $x + 7 - 7 = x + 0 = x$.

Applying $-7$ to the left side of our equation gives us $x$; applying it to the right side gives us $5$. So $-7$ is a transformation from $12$ to $x$, but it’s also a transformation from $12$ to $5$. In a general category, we’d say $x$ and $5$ are isomorphic; in a Coding Category, $x$ and $5$ are equal by how we defined morphisms in that category. Solving this addition problem really amounted to finding an inverse and applying it.

Note that in the case of addition, $+0$ is the identity transformation for every number. In general, however, each object in a category has its own identity transformation. Recall from our first post that the identity transformation for an object starts from that object and goes to the same object, such that we can insert any number of identity transformations before or after it in a sequence without affecting the overall result.

Finding inverses is the key to solving problems

Finding an inverse isn’t just for arithmetic. It applies to solving systems of equations (where the key is finding the inverse of a matrix), optimization problems from Operations Research, differential equations, and problems from process control theory (with one proviso we’ll discuss in a future post). I’ll go even further: finding inverses applies to solving any type of coding problem.

Inverses imply something very strong

Since adding and subtracting numbers is something we can write in code, this is in our Coding Category. By definition, given $x$ we can compute $12$, and given $12$ we can compute $x$. In a deep sense, $x$ and $12$ contain the “same information"—given one, we can compute the other. This is a general property across categories: if an inverse transformation exists between two objects, they can be treated as "the same” thing. If you had either object, you could produce the other at will.

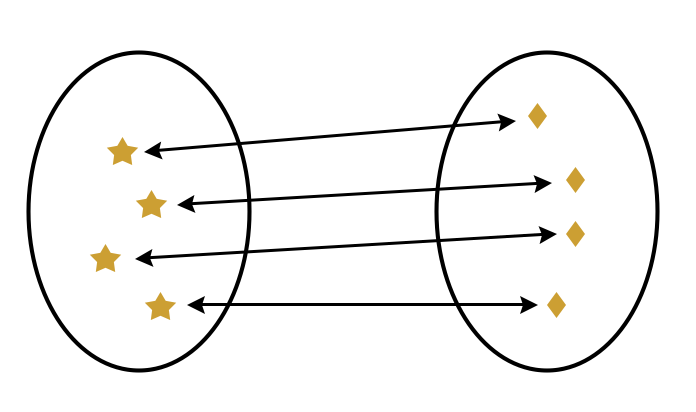

Invertible objects are called “isomorphic” (same shape). You can see this clearly in the Set Category, where objects are sets and morphisms are functions mapping elements in one set to elements in another. The only way to construct an inverse between two sets is if both have the same number of elements and the function maps them one-to-one. The inverse is simply the mapping reversed. Invertible sets have the same number of elements—literally the same shape.

Closing thoughts

There’s something elegant about viewing problem-solving as finding inverses. While we’ve only examined addition here, the idea applies broadly—perhaps universally. There’s something deeply correct about invertible objects being “the same” and containing the “same information.” They aren’t identical, but they are literally interchangeable via transformation in the Coding and Forthic categories.

What if objects aren’t invertible? Then there’s an imbalance—something is missing. In our Coding and Forthic categories, when there’s an imbalance, information is missing and we can’t compute one of the objects from the other (perhaps neither one). Fortunately, we can get around this by thinking in terms of “adjoints.” More on that next time.